writer: Kimmo Tuominen

We are facing big changes in the ways how higher education should be organised. No, I am not thinking about the increasing administrative burden of developing formal aspects of curricula or increased challenges in accommodating more students in the study programmes and planning how they could pass through the programmes within ever decreasing timespan. I am thinking about something much more concrete: the increasing gap between what higher education (in physics) should be and what we typically provide at the physics departments.

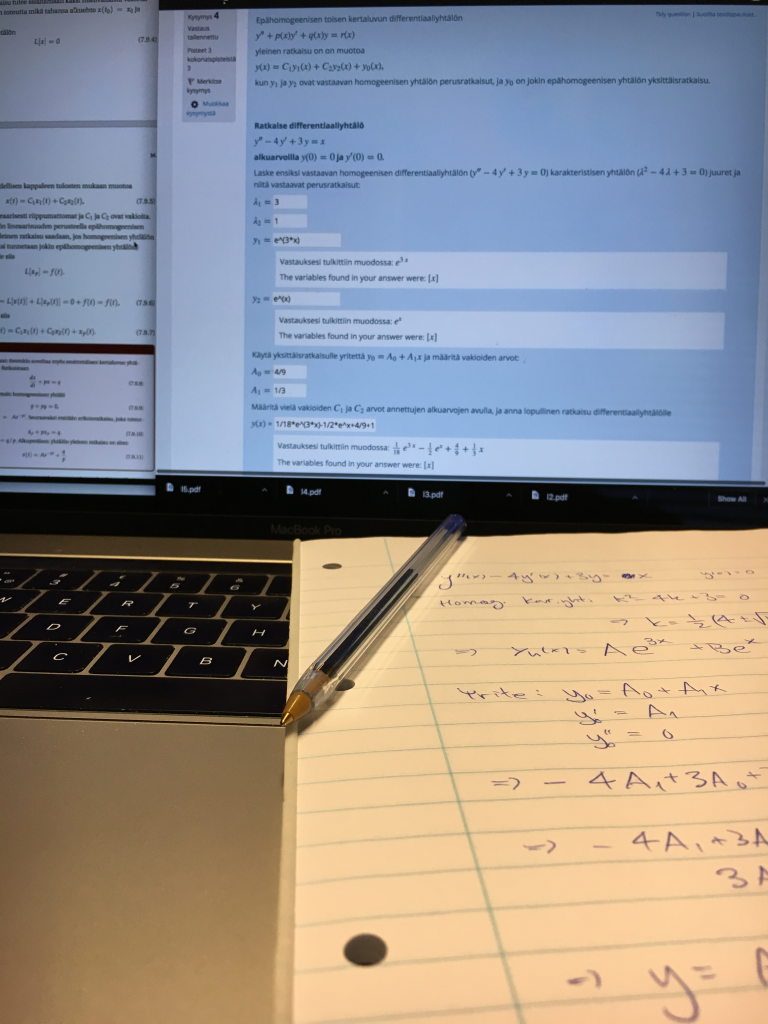

Teaching and learning in schools in general, and in the upper secondary in particular, have undergone big changes over the past decade. Digital era has allowed for new type of learning environments and, for example, full digitalisation of the matriculation exam has been carried out. We can argue how successful all these changes have been, but nevertheless in the universities we need to adapt to this situation: currently the students entering university use computers and other digital devices as the central tool to build their learning experiences. They are used to taking exams within on-line learning environments. For sure, they are far beyond the boundaries of pen and paper. Handwriting is demonstrably important, but let us not be distracted now into analysing parallels between handwriting and cognitive abilities.

Rather, let us focus on the central, if not the defining, element of teaching physics in universities: the lectures. P.A.M. Dirac, while not much of a storyteller, recounted how he struggled to recall upon the Poisson bracket: “I looked through my lecture notes, the notes I had taken at various lectures, and there was no reference there anywhere to Poisson brackets.” Indeed, back in the day, we all went to various lectures to make notes. These became our lecture notes; an invaluable resource besides the course literature. Sometimes the notes were useful and often not. But who would even bother nowadays when, for any given topic, a diverse selection of lecture notes or video materials is already only one Google search away? Does anybody need traditional lectures anymore?

Over the past year next generation coding schools, like Ecole 42 and Helsinki Hive, have attained a lot of visibility in the media. The feature which always gets much attention is the emphasis on the absence of teachers. This statement is somewhat misleading because it is highly dependent on what connotations one fixes to the word ‘teacher’. The schools themselves also boost this statement, although they do admit, that there is a pedagogical team that makes sure the learning environment works and that students are progressing. Probably any school could adapt this as a definition of their teaching staff. However, the essential issue is what this team or staff does — they certainly do not lecture. Rather, learning is focused on peer-to-peer learning and project-based learning. It seems to me, and I have often said this aloud, that big ideas and their implementations go around in cycles. Concepts like ‘peer discussions’ and ‘case-based learning’ are certainly not new. I myself have applied them in teaching already for a decade. Hopefully, given the present new spin, these innovations gain more impetus to penetrate further into teaching in universities and also in other subjects beyond coding.

Abandoning lectures is a long process, as I have personally experienced and witnessed. In my own teaching, this initially amounted to trading much of the teacher’s monologue for peer discussions and various other flipped classroom activities. The big obstacle in these implementations was that anything we do often remains chained to the rigid time and space restraints of the curriculum. Namely, most physics teaching still by default occurs inside an inconvenient lecture theater and in consecutive two 45 minute packages delivered twice a week. This tends to turn any attempted student activity back towards chunks of traditional lecturing and shifts focus away from the student activities. We need to overthrow these ancient habits. I know it may not be easy.

The first small step is to start thinking about it. As a little appetizer, let me offer two statements that everybody (I know) mostly agrees with: First, the most important device to learn physics are the weekly exercise problems. Second, many details of the topics we thought we knew, really sinked in only when we started to think how to explain these topics to someone else.

With these two statements in mind, ask yourself two questions: First, does the amount of time you invest into planning the weekly exercises reflect their importance when compared with the amount of time you invest in preparing your lecture? Second, would you have learned better yourself if you had been given an opportunity to thoroughly discuss the topic you were learning already while you were learning it for the first time? And as an additional bonus question: name one single important thing you have learned at a lecture.

You should spend some time with these thoughts. Because only after realising that lectures where students are the passive by-standers are useless, can one start make progress towards improving the learning results. There are many obvious pitfalls one can fall in here in the attempt of avoiding facing the truth, so let me pave the way past these: an immediate first defence is that bad learning outcomes are simply due to bad students. This is grossly incorrect when viewed from any angle. The good students, implicitly referred to here, are good despite the teaching. They are well motivated, self-guiding and would excel also in absence of the interference of lectures. The bad students on the other hand are the product of incompetent teaching, which has failed to trigger on students’ abilities and needs to learn. Another, a little more advanced, defence strategy is to resort to positive student feedback received on the carefully polished traditional lectures. The positive feedback is of course rewarding, but unfortunately shifts the focus into the teacher activities leaving the students to become passive popcorn consumers following a carefully rehearsed lecture-show. Sustaining old lecturing practices on the basis of student feedback usually serves to detach the development of teaching from development of the learning outcomes; a certainly undesired feature. Once these few obvious pitfalls in thinking are avoided, it becomes obvious that to improve the learning outcomes one should not focus on how the students are or what the teacher is doing, but on what the students are doing.

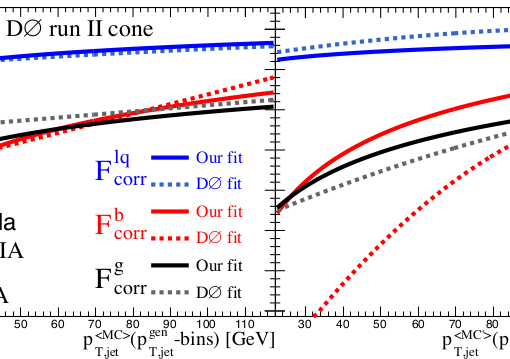

Just for an example, I will cherry-pick few concrete tools, which can be applied in a variety of ways. Over the past years, in physics we have systematically implemented automatically assessed on-line problems on different physics courses. Several universities participate in this effort through the Abacus project. In the bachelor programme in physical sciences in Helsinki university these on-line problems have been gradually taken into use on basic physics and mathematical methods -courses. As a natural development, such exercises are now also crawling into subject study courses as well.

As an exciting development of peer-to-peer learning, in Jyväskylä university physics department a primetime learning concept has been implemented on basic physics courses. In spring 2018 I went to see how this works in practice, how the students respond to it and how it affects the learning outcomes. I had tried case-based learning in my teaching already, and the primetime seemed like a naturally fitting concept within my established course framework. So I copied suitable parts of the primetime learning and made it fit my needs. This turned out to provide a final stretch I needed to stop using traditional lecture halls and stick to traditional time constraints of university teaching. Primetime method also automatically leads to better alignment: to successfully run a course, the learning goals must be spelled out clearly in the beginning, the student activities must be planned to connect well with the learning goals and different types of assessments in the course must be transparent and aligned with the learning goals and student activities.

I strongly encourage everybody to carry out similar experiments. We certainly do not need to lecture to our students. Once you accept this and once you try something else instead, giving up lecturing becomes a no-brainer, really. However, do not think that your workload invested in teaching would be reduced. It will effectively not change that much, but it becomes more meaningful, because reorganising the practices of your teaching will allow you to invest more time into the student activities and these will lead to improved learning results. Perhaps our students will be able to recall the Poisson bracket, or some other key concept, right when they need it.

To summarise: physics education in universities must adapt to the changes occurring elsewhere. Our students are self-guided learners, but they are dependable on the pedagogical team guiding their progress and incubation of new knowledge. We need to revise our views about what to teach, to whom and how. Lectures are certainly not needed. So stop wasting your time and your student’s time. Stop lecturing and think of better ways to progress.